The Origin Story of Israeli Democracy

When the State of Israel was founded, its political structure wasn’t created from scratch—it was a natural extension of how Jews had governed themselves for generations.

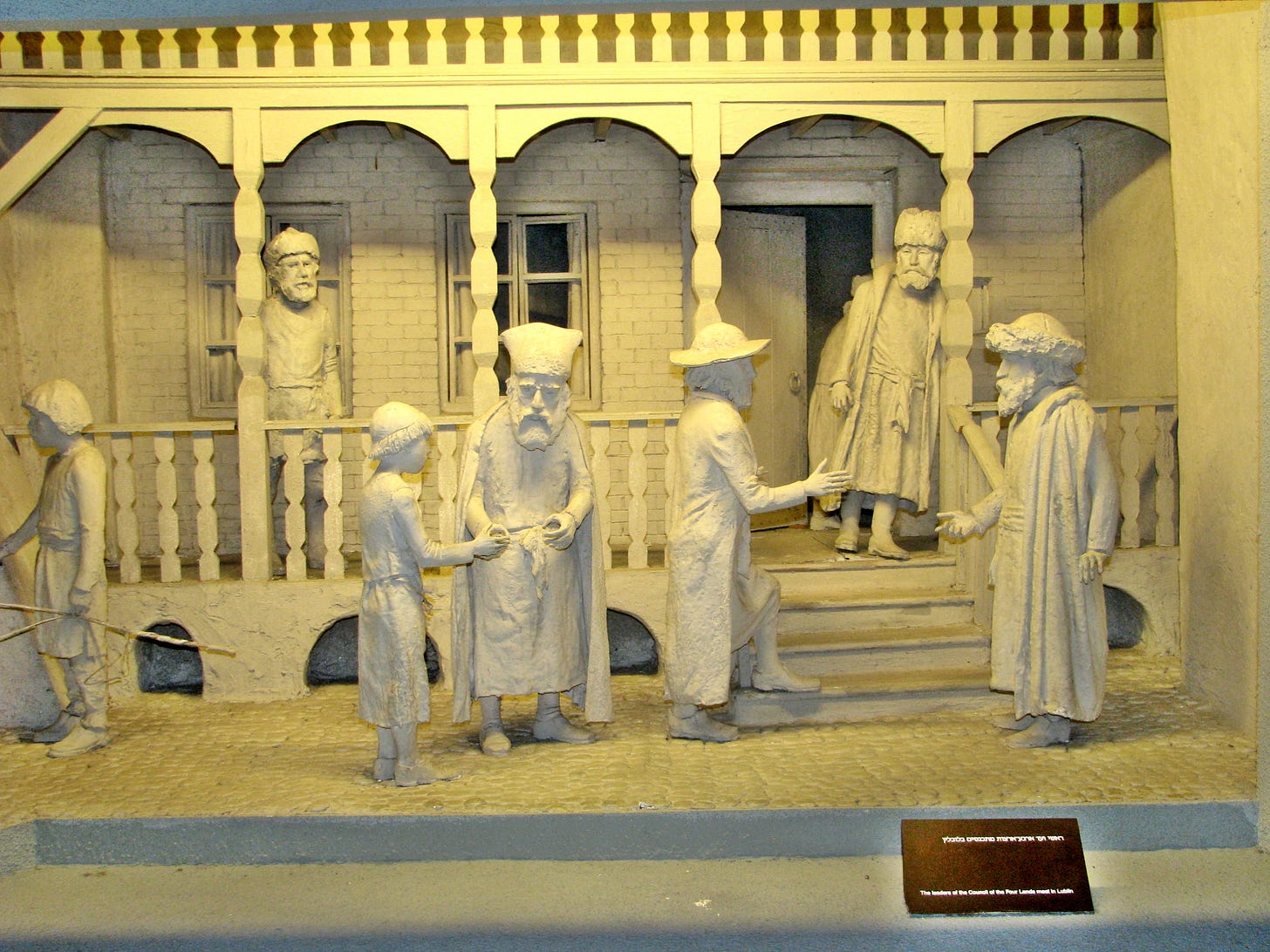

An exhibit at the Diaspora Museum, Tel Aviv, depicting the meeting of the leaders of the Council of Four Lands

For a moment, imagine, that a new state is being established. Within 24 hours of its birth, it is attacked by five neighboring states—countries vastly larger in territory, population, and resources. It will withstand this assault, but one percent of its population will perish in battle. And this is only the beginning of the story. For decades, it will not know a single day of real peace. The hostility of its neighbors will not abate overnight, nor in five years, nor in ten. For at least three to four decades, its mere existence will remain a point of contention, among the region it exists in and in international forums, requiring a near-constant state of vigilance and military readiness.

Meanwhile, this new nation will not have the luxury of a homogenous, stable society upon which to build itself. It will absorb massive waves of immigration, not from affluent, well-educated populations, but from refugees—people fleeing catastrophe. Some will be Holocaust survivors, emerging from the worst industrial genocide in modern history. Others will be fleeing persecution from the very region in which this new country is taking root. Many of them will arrive destitute, traumatized, and one would assume, unprepared for the demands of nation-building.

To top it off, the land they inherit will be devoid of the very things that have propelled so many nations into modern prosperity—no oil, no gas, no great deposits of minerals to trade. Just arid land, some coastal access, and enemies on all sides.

Now, ask yourself: What are the chances that this country will not only survive but sustain a functioning democracy?

If you were designing an experiment in political science, this would be a scenario in which democracy would be expected to fail almost instantly. Under these conditions, history tells us to expect dictatorship, military rule, or perpetual instability. After all, how many democracies have emerged and endured under anything close to these circumstances? The answer, across the 20th and 21st century, is almost none.

Such an experiment is particularly relevant to its time. The mid-20th century was an era of seismic political shifts—the fall of empires and the birth of nation-states. In the wake of World War II, nearly 100 new countries emerged across the globe, from the Middle East to Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, and Latin America. And almost without exception, they all began with the same idealistic script: independence would bring democracy. Free elections, a multi-party system, and an independent press were the foundational promises of most constitutions. The world, still reeling from fascism and the horrors of totalitarian rule, had a strong incentive to believe that self-determination would naturally lead to liberal governance.

But reality was far less accommodating. With very few exceptions—India being the most notable—most of these new democracies failed. Some collapsed into one-party rule, others fell to military coups, some embraced communism, semi-fascism, or some grotesque hybrid of the two. In many cases, democracy was little more than a brief interlude before authoritarian rule reasserted itself, often with mass violence and repression.

Yet the country in question—despite its flaws, despite facing relentless wars, terrorism, and diplomatic isolation—grew from a fragile population of 650,000 people (most of them Jewish refugees) into a thriving nation of nine million, where 20% of its citizens are Arab. Unlike almost every other post-colonial state that emerged in the same period, it has not succumbed to military rule or one-party dictatorship. Against all odds, under circumstances far harsher than any of the other new states, it is somehow this country that has maintains its democracy.

The country, of course, is Israel. But the real question is: Why? If you turn to scholars, you will find two prevailing answers. Both contain elements of truth, but neither fully explains the anomaly that has been Israel’s democracy.

The first proposition given is that there is a tradition of democracy in Judaism. This idea is intuitively appealing—after all, Jewish civilization has long emphasized debate, legal reasoning, and moral autonomy. The notion of human dignity is ofcourse deeply embedded in Jewish scripture. So, is this where Israel’s democratic resilience comes from? The answer is unequivocally no.

Because if we take this theory seriously, we arrive at a patently absurd conclusion. For one, there was no democracy in ancient Jewish governance. The Davidic and Solomonic kingdoms were monarchies—they ruled by divine right, not by the will of the people. The Hasmoneans, despite being hailed as liberators, quickly became Hellenistic-style autocrats, ruling through force, corruption, and hereditary succession. And the texts? Yes there are legal precepts but nowhere in the Bible, the Mishnah, or the Talmud is there a blueprint for democracy. More importantly, liberal democracy itself is a modern invention—a post-Enlightenment phenomenon that only emerged in the late 18th century.

One only needs to look at the religious parties in Israel to understand that its politicians have never been liberal democrats. In fact, in recent years, figures like Bezalel Smotrich (Religious Zionism), Itamar Ben Gvir (Jewish Power), and Yitzhak Goldknopf (United Torah Judaism) have each demonstrated varying degrees of apathy or even animosity toward democracy, both through their actions and policies.

The second theory suggests that the first Jewish immigrants to Ottoman and Mandatory Palestine brought with them the European traditions of liberal or social democracy. Scholars often compare this to the settlers of North America, who imported British parliamentary principles, later enshrined in the American Constitution. By this logic, early Jewish immigrants must have transplanted European enlightenment values—liberalism, democracy, and civic governance—into what would become Israel.

This argument is more plausible than the claim that democracy is rooted in Jewish religious texts, but it still falls short. Most Jewish immigrants did not come from democratic societies. They did not arrive from Britain, France, or Norway, but from Czarist Russia, communist Russia, interwar Poland and Hungary, and fascist-aligned Romania and Italy. Many were refugees from Nazi Germany and Nazi-occupied Austria and Czechoslovakia. These were not places that nurtured democracy; they were regimes of authoritarian rule, oppression, and ethnic persecution. If political inheritance shaped Israel’s governance, its founders would have carried with them the legacy of autocracy, not democracy. The notion that Israel’s democratic character is merely a byproduct of European political culture collapses under even the slightest scrutiny.

The reason that Israeli democracy developed does have to do with Jewish history though, but it didn’t emerge from scripture or origin but from historical and social realities. For centuries, European Jews—who made up 85% of global Jewry before the Holocaust—operated under self-governing communal structures. The kahal functioned as a political entity, managing internal affairs, resolving disputes, and negotiating with external rulers. While Jews lacked sovereignty until 1948, they had long practiced the mechanics of self-governance, making the transition to statehood less of a leap and more of a continuation.

Political scientist Shlomo Avineri points out that whether Jews lived under Muslim or Christian rule—from Spain to France, or later in Germany and Eastern Europe—they prioritized two things: 1) a place of worship and 2) a space where children could learn about Jewish historical norms. They quickly realized that the only way to achieve this without a state or political power was through a voluntary electoral system. European Jewish communities, whether large or small, were established only when a sufficient number of Jews assembled and chose to form a community by electing members as chairmen, secretaries, or treasurers.

This system wasn’t dictated by rabbinical authority but by the community’s ability to elect its own leaders. Sometimes those leaders were rabbis, sometimes they weren’t. Some communities were more egalitarian, others more hierarchical. Some functioned as oligarchies, allowing the same families to retain power, while others imposed limits to prevent any single family from dominating leadership. But in every case, these Jewish communities operated as miniature city-states—a kind of polis, if you will.

In other words, Jews may not have had a state, but for centuries, they had been practicing community politics in ways that closely resemble modern elective democracies. Their systems weren’t free from political infighting or factionalism—on the contrary, they had all the familiar virtues and dysfunctions of democratic life seen in Israel. Disputes over leadership or the community rabbi often led to secessions, with dissenters moving across the street or up a nearby hill to establish a “rival” community. Through this process, Jews became adept at electing leaders, building coalitions, challenging opposition, and establishing a basic framework for voluntary taxation.

In some countries, like the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Jews established larger regional councils, such as the Va’ad Arba’ Aratzot (Council of the Four Lands). Meeting annually in Lublin, these councils functioned as de facto political parliaments, setting communal policies despite lacking sovereignty. As early as the 17th century, they mandated basic education for young boys to ensure literacy in Hebrew, implemented voluntary taxation, and reinforced communal solidarity. When disasters, pogroms, or wars struck one community, others pooled resources to help rebuild or integrate those affected into new communities.

By the time the Zionist Movement was founded in 1897, Jews knew exactly what to do. The First Zionist Congress established elections—and held them. When the first Jewish olim (immigrants) arrived in the Land of Israel in the late 19th century, they built agricultural colonies and then a garden suburb they named Tel Aviv. They didn’t need to invent self-governance from scratch—this was how they had been operating for generations. They elected secretaries for the first kibbutzim and municipal leaders for Tel Aviv. They knew how to allocate and collect taxes, often through voluntary means. From the Ottoman era to the British Mandate, the Jewish community in Palestine systematically laid the foundations of self-government.

When the State of Israel was founded, its political structure wasn’t created from scratch—it was a natural extension of how Jews had governed themselves for generations. David Ben-Gurion, already Chairman of the Jewish Agency, became Provisional Prime Minister. Ministers were drawn from existing Jewish institutions in Mandatory Palestine. Independence was declared, war was fought, and the next step was elections. The political parties were already in place—various labor factions, bourgeois liberals, and left-wing Zionist worker movements. Israeli democracy wasn’t shaped by abstract constitutional models but by the lived experience of Jewish self-governance.

From the Passover Seder. "In every generation, to our fathers and to us, there have arisen those who would destroy us, but the Almighty, blessed be His name, saves us from their hands!"

Anyone who can write the the Netanyahu government threatens the very democratic institutions that have allowed our Jewish democracy to endure reveals a complete misunderstanding about democracy and turns his argument about the harbingers of Israelis democracy in years of exile into a pastiche. Not to mention the slander of Smotrich and Ben- Gvir in which you indulge so whimsically. Yes, Israel's yishuv origins prepared it for successful democracy, but the nature of Jewish self-government and the wrangling endemic to it goes all the way back to the Bible. The drawbacks of current Israeli democracy have more to do with that, exemplified in the extreme proportional representation of their electoral system, the highly personalized system of leadership endemic to Jews for three thousand years, and the stranglehold the old Yishuv elites and its descendants have on all the extra-governmental institutions of the country.